AI Generalist vs Specialist: Who Wins in the Age of AI?

The world of work is undergoing a profound transformation. For decades, the traditional wisdom was clear: specialists build deep expertise, and generalists provide broad context.

Specialists earned higher pay, commanded niche roles, and organizations organized work around clearly defined roles. But as AI reshapes how knowledge is created, applied, and scaled, that old model is being challenged.

In today’s AI-driven landscape, versatility and adaptability increasingly matter as much as deep technical depth. The million-dollar question is:

In the AI era, which matters more – deep specialization or broad generalization?

And more importantly, how should individuals and organizations think about skills, roles, and hiring?

From Slow Change to Rapid Reinvention

Before AI became mainstream, technology evolved slowly.

Specialists such as system architects, database experts, front-end developers could build deep domain knowledge and rely on that expertise to drive predictable outcomes. A Java expert in 2010 could reliably deliver high-performance backend systems because the technology stack was stable for years.

But AI fundamentally changed that dynamic.

AI technologies evolve in months, not years. New models emerge every quarter. Tools that automate deep learning pipelines, conjure production-ready code, or help design user workflows now exist – often before anyone is an expert in using them.

This rapid pace means that specialists rarely get the luxury of working in stable environments for long. The problems of today require fluidity to learn, unlearn, re-learn, and integrate multiple domains.

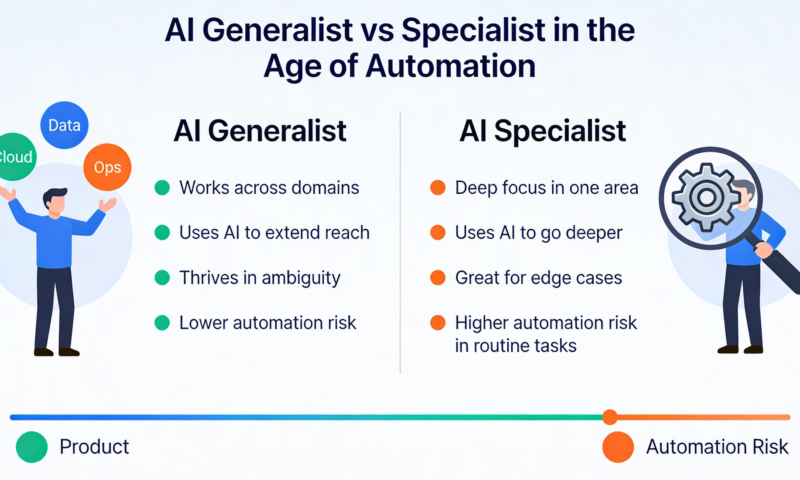

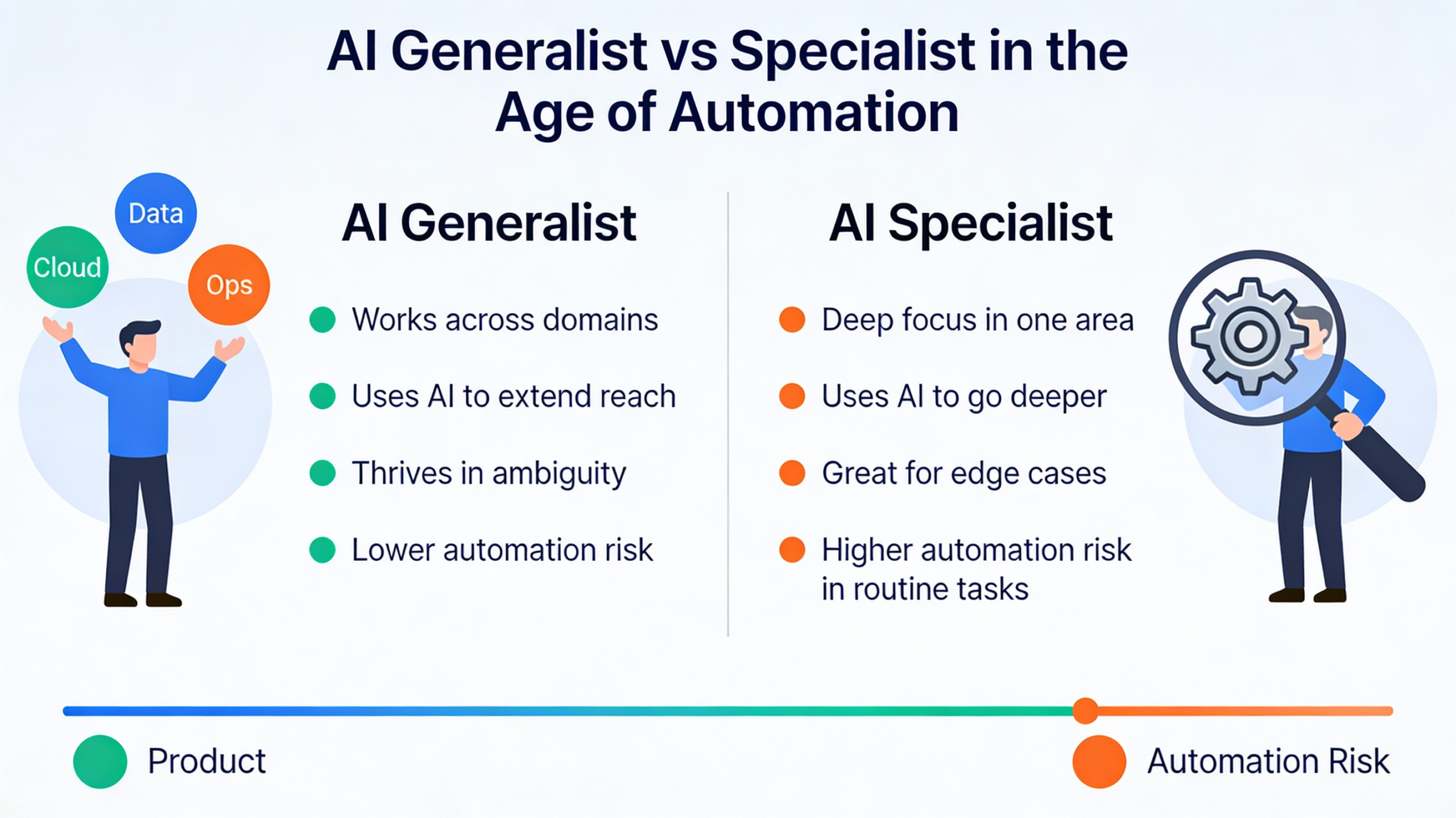

Why AI Favors Generalists

A recent VentureBeat article argues that the age of the pure specialist is waning and that generalists with range, adaptability, and decision-making can thrive in AI environments.

The key reasons cited:

🔹 Speed of Change

New technologies and frameworks emerge so quickly that specialists built for one stable stack struggle to stay current.

🔹 Breadth Over Depth

Problem-solvers who understand multiple layers from product design to data infrastructure to user experience are better equipped to leverage AI tools for real business outcomes.

🔹 End-to-End Ownership

Generalists often take accountability for outcomes, not just tasks, enabling faster decisions with imperfect information – a hallmark of modern AI work.

In essence, the article suggests that AI compresses the cost of knowledge, making it easier for generalists to perform tasks that once demanded highly specialized training. At the same time, it creates a premium on learning agility, adaptability, and cross-functional thinking.

What Makes a Strong Generalist in the AI Era?

Drawing from synthesis across industry thought:

✔ Breadth with Depth: Not shallow breadth, but deep fluency in a couple of domains plus competence in many.

✔ Curiosity & Adaptability: The ability to quickly learn new technologies and integrate them into solutions.

✔ Agency & Ownership: Acting decisively even with incomplete information.

✔ Cross-Disciplinary Thinking: Connecting dots across engineering, business, design, and operations.

Generalists excel not because they know everything, but because they can connect everything.

But Specialists Still Matter – Especially in High-Stakes Domains

While the pendulum may be swinging, specialization still has critical value particularly where precision, domain depth, and contextual understanding are paramount.

In technical domains like:

- Medical AI and imaging

- Financial risk and regulatory compliance

- Security, safety, and ethical AI engineering

specialists often outperform generalists because their deep expertise enables them to make fine-grained judgments and avoid catastrophic errors that a broad but shallow understanding might overlook.

Specialists are also harder to replace with AI alone because many complex domain problems require years of tacit knowledge, situational judgment, and context that AI hasn’t mastered.

AI Isn’t Killing Specialists – It’s Expanding Roles

AI lowers the barrier for execution and routine tasks, but it raises the bar for judgment and context. This means:

🔸 Specialists can now leverage AI as a force multiplier – AI handles repetitive and foundational work, while specialists focus on nuance and innovation.

🔸 Generalists can apply AI tools to bridge gaps between domains and lead cross-functional initiatives.

🔸 The true winners are often T-shaped professionals – those with one or two deep competencies and a broad understanding across related areas.

The Balanced Reality: Not Generalists vs Specialists – But How They Work Together

While some voices suggest generalists are the clear winners, the actual landscape is more nuanced.

AI enables:

- Generalists to do more with less (launch prototypes, explore new areas, coordinate teams).

- Specialists to focus on high-value, high-impact tasks that AI cannot fully solve.

The most successful organizations adopt a hybrid talent model:

- Use specialists for deep technical work

- Use generalists to integrate, orchestrate, and guide business impact

A useful way to view this is: AI is making “T-shaped” and “polymath” talent structurally more valuable.

AI doesn’t make specialist knowledge obsolete – it makes specialist knowledge more productive, and generalist judgement more valuable.